I think the journey time was to allow for gravitational flipping to increase the speed to catch the comet so as to save having to use lots of fuel thereby increasing the payload weight. This is the technique they used to propel the Voyagers through the Solar System and the fuel is then used to manoeuvre the craft.

The journey time was I believe to use gravity assist to sling shot the craft fast enough to catch up to the comet. The technique was used with the voyager crafts to get them to journey through the Solar system. This was done to reduce the amount of fuel on board which would have increased the payload weight and taken up space. The fuel on board is used to manoeuvre. http://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/61960/what-is-the-fastest-a-spacecraft-can-get-using-gravity-assist. sorry for repeat but had not completed post.

Thanks for that, Brian. Interesting post and link. I realised it was because of Voyager-style sling-shotting but it still seemed to be taking the 'scenic' route! In the simulation on the Rosetta website the probe seemed to come back almost to Earth which made me wonder if it wasn't taking a route that could have been made a bit shorter. But what do I know. I'm amazed at how they managed to model the flight path so precisely, no matter how long it took.

PS: I think there should be an 'Edit' button on your posts allowing you to go in and change/add stuff, but please let me know if not.

I believe that Rosetta has used 4 gravity assists to get to the comet - 3 of the Earth and 1 of Mars. As Brian says, it was the only way of getting to the comet and, most importantly, exactly matching its velocity at the rendezvous point without using masses of fuel.

I still remember my text book on this from university - Danby's "Fundamentals of Celestial Mechanics". I'm itching to write another equation 😉

Andy there is but I think I left it to late.

I’m itching to write another equation 😉

Oh, go on, Mike. Treat yourself - and us!

http://www.theguardian.com/science/across-the-universe/2014/aug/06/rosetta-comet-67-churyumov-gerasimenko-european-space-agency Blog from Stuart Clarke

Great article from Stuart. I remember the live TV programme about the Giotto mission to Halley's Comet very well. It certainly didn't make for good TV... the build up was all about seeing these fantastic images of a comet's nucleus for the first time... and all we saw was a few coloured blobs on a screen, which looked like an image from a ZX Spectrum computer!

Some expectation management was certainly required!

Of course, when the data was finally analysed, they got some wonderful images. Such as...

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="508"] HMC 68 Image Composite. Comet Halley. 14 March 1986.[/caption]

HMC 68 Image Composite. Comet Halley. 14 March 1986.[/caption]

... but note the date on the image... over 4 years later!

It takes time to analyse all of this data and it's certainly not conducive to a live TV programme.

Oh, go on, Mike. Treat yourself – and us!

If you insist 🙂

You can look at this as a three-body problem e.g. the Sun, the planet and the satellite. Of course, there is no useful solution to the three-body problem, despite hundreds of years of research... however, you can create solutions if you reduce the scope of the problem.

There is a solution known as the Tisserand criterion, which works because the mass of the satellite (or comet, or other small body) is tiny in comparison to the Sun and a planet.

The satellite's orbital energy is determined entirely by its major radius a. The approximate conserved energy of the satellite before and after its close approach to the planet is:

E = - 1 / (2a)

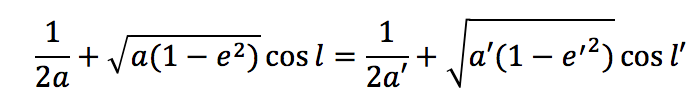

If we let a, e and l be the major radius, eccentricity and inclination angle of the satellites orbit before the close encounter with the planet and a', e' and l' be the corresponding parameters after the encounter, then the Tisserand criterion states that:

(1 / (2a) ) + sqrt ( a ( 1 - e^2)) cos l = (1 / (2a') ) + sqrt ( a' ( 1 - e'^2)) cos l'

This means that a spacecraft can make use of a close encounter with a moving planet to increase (or decrease) its orbital major radius a and, hence, to increase (or decrease) its total orbital energy.

😉

(1 / (2a) ) + sqrt ( a ( 1 – e^2)) cos l = (1 / (2a’) ) + sqrt ( a’ ( 1 – e’^2)) cos l’

Mike, for Christmas we'll get you the mathematical formula plug-in.

I remember the live TV programme about the Giotto mission to Halley’s Comet very well. It certainly didn’t make for good TV

Crumbs, I remember that, too - and the feeling of 'Is that it???' I remember thinking even Patrick Moore seemed to be pretending to be more excited than he really was. Though he would have realised the value and significance of what we were seeing, he would have had to admit it was underwhelming as television.

Mike, for Christmas we’ll get you the mathematical formula plug-in.

Difficult to follow, isn't it?

Try this...

Mike on the formula rampage again 🙂

Andy, I was trying to think up an analogy for sling shot acceleration going around the same mass more than once. I wonder if the track and field event, Hammer Throw might help as one?

Only just catching up with the amazing Rosetta mission. I'm a little bit shocked though. Is that really all dirty ice? It looks more like a piece of Mars rock . I am still yet to read up more on it, though.

I couldnt help myself but upon seeing the close up near hi res image of of the comet, the first words that came out of my mouth was a famous Arnie line from Predator....I cant say the line here though, but if any of you saw that film, I think you know what I'm talking about...I am sure Brian does!

Seriously, that is one bizarre object. Any theories yet on how the hell it got that way?